Ada Bryon was born in London on December 10, 1815. She was the daughter of the infamous Lord Byron and the Baroness Anabella Milbanke. While the pair was perhaps the most intelligent couple in Europe, they were incredibly different in temperament. Lord Bryon was one of the greatest poets while Baroness Milbanke was one of the most prodigious mathematicians. Lord Bryon was known for his scandalous, wild exploits while Baroness Milbanke was austere and religious. The couple split 5 weeks after Ada’s birth.

Ada spent her childhood undergoing a strict and rigorous educational plan. Ada’s true interest in mathematics seems to have been ignited after a meeting with Charles Babbage. Charles Babbage was the son of a wealthy banker and showed genius in mathematics at an early age. After graduating from Cambridge, his bright career was postponed for many years while he was unfairly denied research positions at several universities. During this period, Babbage lived off his family’s wealth and continued to produce papers on a variety of topics.

Babbage’s interest soon turned to produce trigonometry and logarithmic table books. These books were enormously valuable, especially to militaries for their use in ship navigation. The tables were produced by assigning the calculations to mathematicians to write down into a manuscript and then copying the manuscript by the printing press. The production of these tables was incredibly laborious and time-consuming, with many different opportunities for errors to slip in. Babbage’s focus turned to the design and invention of a mechanical calculator that could use Isaac Newton’s “method of differences” algorithm to automate the work of these mathematicians.

At age 17, Ada travelled from her mother’s country estate to London for her debutante season. While at a party thrown by the philosopher and mathematician Charles Babbage on behalf of his 17-year-old son, Ada was introduced to the 41-year-old Charles due to their common interest in mathematics. Babbage showed Ada the prototype of his “Difference Engine” machine. The Difference Engine was supposed to be a special-purpose calculator that would inspire Babbage’s design for a Turing-complete universal computer.

Following the meeting with Babbage, Ada kept up a friendship with Babbage while spending the next several years getting married and raising 3 children. In 1839, Ada wrote Babbage asking about a recommendation for a tutor in mathematics. Babbage recommended the preeminent logician Augustus De Morgan. Augustus De Morgan was a close friend of George Boole, the inventor of Boolean algebra, making Ada only two degrees of separation from another major figure in the history of computing. De Morgan’s first subject for Ada was calculus which Ada quickly excelled in.

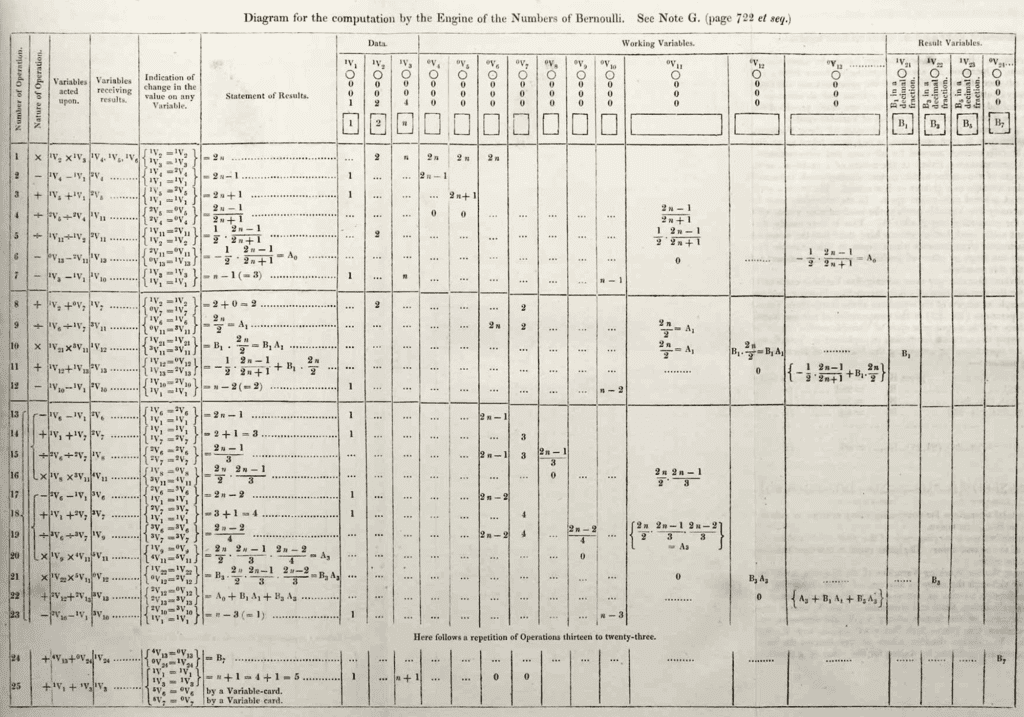

Babbage had attempted to secure funding for his idea for a purely mechanical Turing-complete universal computer but was rebuked by funding agencies in England. In 1840, Babbage gave a lecture on the idea in Italy. A young engineer named Luigi Menabrea attended the lecture, taking notes, and later publishing them in French. In 1843, Ada decided to translate the notes into English and incorporate her own notes into the paper. Ada spent several months publishing the notes which are considered her magnum opus.

Ada’s notes are incredibly thorough and demonstrate excellent technical knowledge. More importantly, Ada gives original insights to many of the most important ideas in computing. Among Ada’s most prescient comments: “the nature of many subjects in that science are necessarily thrown into new lights, and more profoundly investigated.” She also famously makes an important claim about the possibility of artificial intelligence: “The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform…. Its province is to assist us in making available what we are already acquainted with.”. Another original insight found in Ada’s paper is the idea that the Analytical Engine could manipulate more than just arithmetic numbers with special reference to musical notes. This idea does not seem to be present in Babbage’s work and is unique to Ada.

After the publication of Babbage’s notes, Ada proposed to be in charge of Babbage’s Analytical Engine project including securing funding and hiring engineers. Babbage’s role would be to supervise the technical details. As the record appears in their correspondence, it seems that Babbage mostly agreed to her terms. This was an unusual decision on Babbage’s part, as he was long noted for his temperamental and domineering character. Ada was herself surprised and wrote that “I have never seen him so agreeable, so reasonable, or in such good spirits!”.

The two continued to think up schemes for funding but Ada had to delay more serious efforts on the project as her health became a problem. Over the next several years, Ada’s health declined precipitously and she was tragically diagnosed with cancer. Today, it is widely believed she suffered from ovarian cancer. Ada tried a variety of cures but eventually realized that death was imminent. She called on her friend Charles Dickens to read a story about death from one of his books. In her final months, Ada asked to be buried next to her late absentee father which deeply angered her mother and husband. Ada had long been an admirer of her father despite her mother’s attempts to inculcate the opposite.

Ada survived longer than expected, several months after falling into serious decline. Nurse Florence Nightingale, another friend, said of her passing on November 27, 1852: “They said she could not possibly have lived so long, were it not for the tremendous vitality of the brain, that would not die.”. Ada Lovelace was 36 years old.

Ada’s final wish was to have her correspondences collected and organized. From these writings, Ada appears to have had brilliant and systematic views in a variety of fields of knowledge. In perhaps her most perspicuous moment, she writes in one letter to a friend: “It does not appear to me that cerebral matter need be more unmanageable to mathematicians than sidereal & planetary matter & movements; if they would but inspect it from the right point of view. I hope to bequeath to the generations a Calculus of the Nervous System.”. These ideas preempted similar ideas from George Boole by a decade and many other figures in psychology by much longer.

The provenance of the idea of computation is a complicated and difficult issue. It seems that Alan Turing was not aware of Babbage and Ada’s work on the Analytical Engine in 1937 when he published “On Computable Numbers”. Ada was clearly one of the most brilliant minds in history. Her reflections on information processing and artificial intelligence are completely original and far ahead of her time. The bulk of the credit for designing the blueprints of the Difference Engine and the Analytical Engine belongs to Babbage but Ada had an important role in clarifying these blueprints. In summary, Ada Lovelace didn’t invent the computer but had she not tragically died so young, she might have played a very large role in the construction of the first computer or in the development of the idea of universal computation. In many ways, Ada saw deeper than Babbage to the potential of the Analytical Engine. Had Ada lived longer, she might have made the contributions of Turing or Von Neumann.